Previous episodes of Rambling from Red Shift have taken a look at rare or infrequently seen complaints, just for a change I have decided to look at the assessment of a leading cause of emergency calls – the common fall. Also I have chosen to write it as an educational piece rather than a series of links to further reading as I was unable, without spending a lot of time undertaking research, to find an easy to read, detailed article which described assessing falls from a paramedic perspective.

The World Health Organisation defines a fall as ‘an event which results in a person coming to rest inadvertently on the ground or floor or other lower level. Falls actually represent the second leading cause of accidental injury death worldwide – in WA, they are the fourth most common cause of community death and second most common cause of community injury hospitalisation. And, when else can you use such a great mnemonic – SPLAT – than when examining the history of a fall?

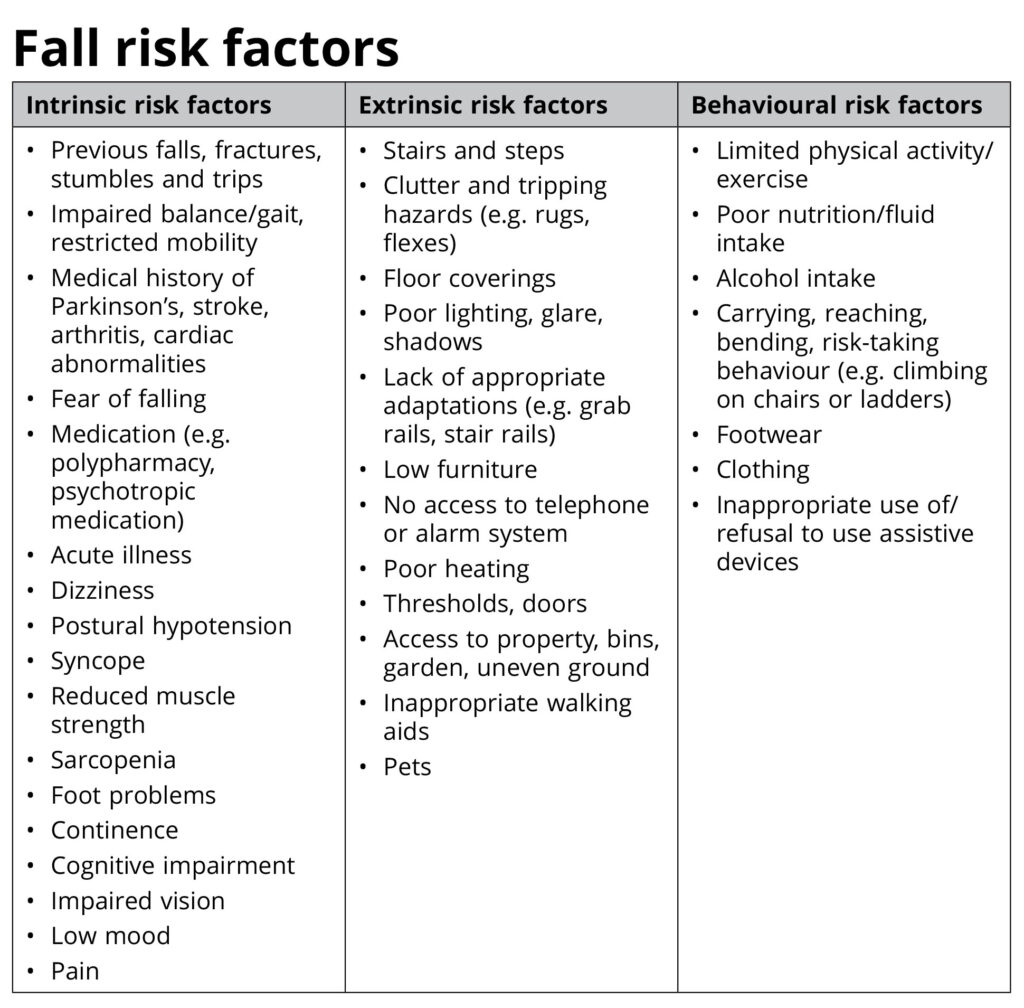

It has been recommended that the term “mechanical fall” is not an appropriate term to use when describing a fall – it implies that a benign aetiology for an older person’s fall exists and is open to interpretation on what differentiates a mechanical from a non-mechanical fall. While there are common risk factors associated with falls (described in the attached table), falls in older adults often result from the dynamic interactions of risks in all categories. All falls patients need a thorough evaluation to determine the aetiology of the fall to impact outcomes.

A thorough and careful physical examination combined with a thorough falls and clinical history assessment should be undertaken while maintaining a high index of suspicion. Easily missed injuries, such as spinal fractures, delayed presentation of a previous head injury and rib fractures can have serious long term consequences for an older person – for example the relatively minor rib fracture may result in pulmonary contusions and we haven’t even started to consider the effect of the loss of independence and confidence. In fact, every rib fracture increases the risk of dying by 15 per cent in frail older people.

In addition to the usual primary and secondary survey undertaken – considering the possible intrinsic factors of the fall and potential for traumatic injuries – the assessment of falls in older adults should include:

Review of body systems:

- Cardiovascular (including postural hypotension assessment and 12-lead ECG). Red flags for syncope seen in a 12-lead ECG include conduction abnormalities (such as complete right or left bundle branch block, atrial fibrillation or any degree of heart block); evidence of a long or short QT interval or any ST segment or T wave abnormality;

- Respiratory system. Risk factors specifically related to the physical and psychosocial effects of COPD include muscle weakness, impaired postural balance, use of supplemental oxygen, increased ‘fear of falling’ and heavy smoking history;

- Gastrointestinal;o Genitourinary. Lower urinary tract infections are a potential risk factor for falls. Published reports have suggested that urgency, frequency, nocturia, and urinary incontinence are associated with an increased likelihood of falls in older adults;

- Neurological. Considering stroke and TIA as potential causes of falls along with dementia and cognitive impairment – patients with dementia are more likely to fall and more likely to sustain an injury. Confusion is routinely encountered with older adults who have fallen and could be an indication of an acute pathology presenting as delirium. New onset confusion can be due to physiological changes resulting from a wide variety of causes, majority of which cannot be identified in the out-of-hospital environment.

- Musculoskeletal. Falls are a more frequent cause of spinal cord injury in the older patient and Central Cord Syndrome (CSS) may occur in older patients with degenerative spinal disease who sustain hyper-extension of the cervical spine during the fall – these patients may also present without any bony injury;

- Hair, skin (look for integrity, lesions and pressure areas) and nails; and

- Mental health, including anxiety, depression and fear of falling.

History of the fall – this is where the SPLAT mnemonic comes in. The circumstances surrounding a fall are a critical part of care, because a fall may be the first and main indication of another underlying and treatable problem. Older people who fall are more likely to fall again, and a previous fall is a strong risk factor for future falls and falls injuries. The SPLAT mnemonic examines the history of the fall:

- Symptoms prior to and at the time of the fall;

- Previous falls, near falls and/ or fear of falling;

- Location to identify contributing environmental factors;

- Activity the person was participating in when they fall; and

- Time of the day the fall occurred (falls in the morning could be due to postural hypotension and later in the day could be due to fatigue.

Functional assessment. Mobility should be considered to help exclude injury; determine if mobility is a factor contributing to the fall; and ascertain the patient’s ability to function safely at home following the call;

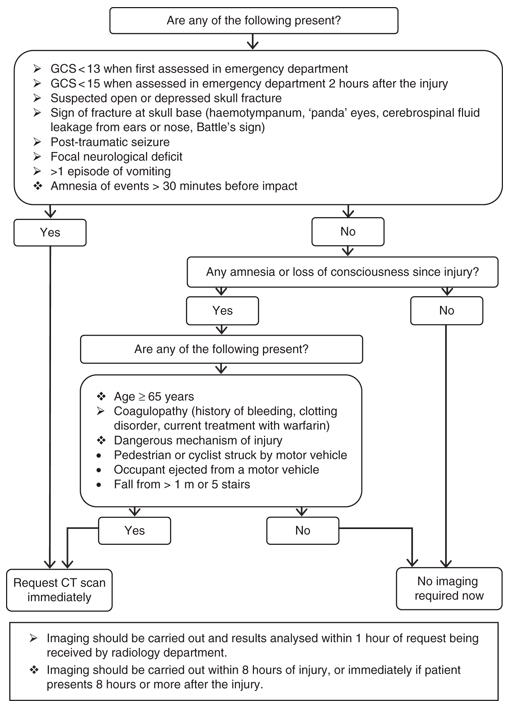

Review of medication. Many medicines cause postural hypotension and may contribute to over 20% of extrinsic falls. Common causes are cardiac drugs, urological drugs and neuropsychiatric drugs. Patients on anticoagulant, antiplatelet therapy and/or patients with a known coagulopathy (e.g. alcohol dependent persons) are also at an increased risk of intracranial, intra-thoracic, intra-abdominal haemorrhage – (guidelines for indications for CT scans for patients with head injuries are also attached);

Other considerations including care plans; extrinsic factors; safeguarding; social context; referral; and falls prevention.

A ‘long lie’ is usually defined by someone who has been on the floor for over one hour and has been unable to get up. Anyone who has experienced a long lie is at a higher risk of complications, such as pneumonia, pressure areas, rhabdomyolysis, dehydration and hypothermia. A few years ago I attended an obese patient who had been on the floor for six hours with a fractured hip – 15 minutes after moving her she went into cardiac arrest – we did get ROSC on way to hospital – it was thought the arrest was caused as a result of the crush injury and compartment syndrome from laying on the floor for that long and subsequent movement.

Older adults can present with major trauma with seemingly minor mechanisms of injury and kinetic energy transfer with low level falls being a leading cause of severe injury – these patients may benefit from being conveyed directly to a Trauma Centre.

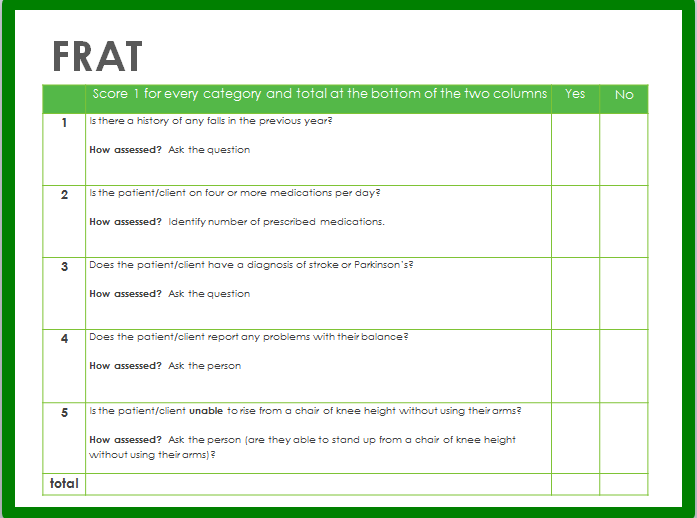

The attached Falls Risk Assessment Tool was developed to provide a quick assessment of falls risk for older adults outside hospitals – examining falls history, medications, medical history, stability and core strength. Scores of three or more are classed as high falls risk.

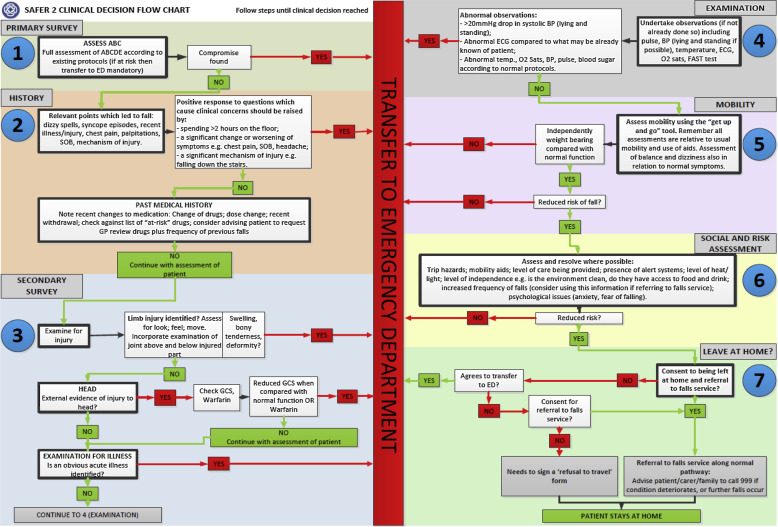

A more detailed assessment tool for paramedics was developed as part of the SAFER2 study – an examination of a new clinical protocol which allows UK NHS paramedics to assess and refer older people who have fallen, and do not need hospital care, to community-based falls services.

Further information on the research protocol and trial can be found here:

https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/2/6/e002169

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0196064417300161

Decisions on whether to manage a patient at home should be made following a comprehensive history, clinical assessment and examination. Decisions on the best management should be made on a risk vs benefit basis and should be a shared process, including the patient, their family and carers, other health and social professionals and those holding power of guardianship for the patient. For those choosing to leave the patient at home, they should be provided with appropriate advice and, if possible, a referral to a GP or fall specialist. An example of health advice following a fall, from the WA Department of Health, can be found here:

Perth has its own Falls Specialist Service – designed to assist older adults living in the community to identify and reduce their risk of falls. The service targets older adults over 65 who are at risk of a fall, or have already experienced a fall and would benefit from a detailed assessment of their risk of falling. Information, and contact details, for this service can be found here: