Pelvic trauma used to be a significant cause of death, but advances in integrated, inclusive trauma care have resulted in a significant reduction in mortality. A review into the introduction of a multi-disciplinary approach including: improved triage; early pelvic binder application; early administration of blood and blood products; adherence to algorithmic pathways; screening with focused sonography (FAST) and early operative intervention by specialist pelvic surgeons; saw a reduction in mortality from 20 per cent to 7.7 per cent. Patients now usually die as a result of concomitant injuries rather than isolated pelvic fractures.

Relatively uncommon – accounting for only three per cent of skeletal injuries – pelvic fractures frequently result from high velocity mechanisms such as motor vehicle crashes (MVCs), pedestrians hit by motor vehicles, motorbike and bicycle collisions, falls (both low and high falls) and crush injuries. As disruption of the pelvic ring requires a high energy decelerative force of approximately 50 km/h, patients with suspected pelvic fractures will almost certainly have organ injuries and further sources of haemorrhage.

The sacrum, coccyx and the innominate bones – ilium, ischium and pubis – together create the pelvis. While the sacroiliac joint (between the sacrum and ilium) is the strongest joint in the body, the pubic symphysis is less so, being the weakest link in the pelvic ring. The strength and stability of the pelvis is dependent on the ligaments that connect the sacrum to the other pelvic bones, compression and shearing forces can significantly disrupt these ligaments.

Haemorrhage is the major reversible factor of pelvic fracture mortality, with bleeding in pelvic fractures occurring from three sources: arterial, venous (more common) and cancellous (from bone marrow). Additionally, injury to nerve pathways can result in bowel, bladder and sexual dysfunction.

For a pelvic fracture to be considered unstable, there needs to be a fracture in two places of the ring. There are three forces involved in the pelvic ring fractures:

- Lateral compression (LC): this is the most frequently experienced and occurs in association with abdominal, thoracic and cervical injuries. LC results from side impact and causes inward rotation of the hemi pelvis and rotational instability, which can result in an open-book fracture on the side opposite the impact. If the force is insufficient to open the pelvic, organ damage can occur from bony fragments;

- Anterior posterior compression (APC): the force is directed either anterior posterior or posterior anterior, resulting in ligamentous injuries with possible pubic rami fractures (open book). APC injuries are those usually associated with arterial damage to the internal iliac artery along with bleeding from injury to the pelvic veins and pre sacral venous plexus;

- Vertical shear (VS): the force is transmitted through the femurs and can produce varying injury patterns, for example ipsilateral disruption of all ligaments restraining the hemi pelvis, from landing on an extended lower limb after falling from a height or frontal-impact MVCs where the leg is extended on the pedal. The VS mechanism does not usually involve major arterial injuries.

Haemorrhage from pelvic fractures has been likened to bleeding into a free space, potentially capable of accommodating the patient’s entire blood volume without gaining sufficient pressure-dependent tamponade. While an adults’ average pelvic volume is approximately 1.5 litres, disruption of the pelvic ring can dramatically increase this volume – the retroperitoneal space can accumulate five litres of fluid with only a small increase in pelvic pressure.

Other organs that can be damaged by pelvic ring injuries include genitourinary and gastrointestinal systems, vagina, prostate and the lumbar and sacral plexuses, for example, 16.5 per cent of patients with pelvic trauma experience damage to intra-abdominal organs, frequently the spleen, liver and bowel.

Pre-hospital assessment of a pelvic fracture is extremely difficult, as deformities can be difficult to detect, especially if there is no obvious external haemorrhage. While the outdated method of ‘springing the pelvis’ is no longer current practice – shown to have both poor sensitivity and specificity, simply compressing the pelvis can cause further haemorrhage and should not be part of the pre-hospital management regime either. For conscious patients, gently palpation of the bony structures of the pelvis and lower spine will identify any tenderness and possible presence of pelvic fractures. While assessing the pelvis for mobility can be considered appropriate, it should only be performed once, ideally by the most senior trauma doctor present and is usually deferred until arrival at the Emergency Department.

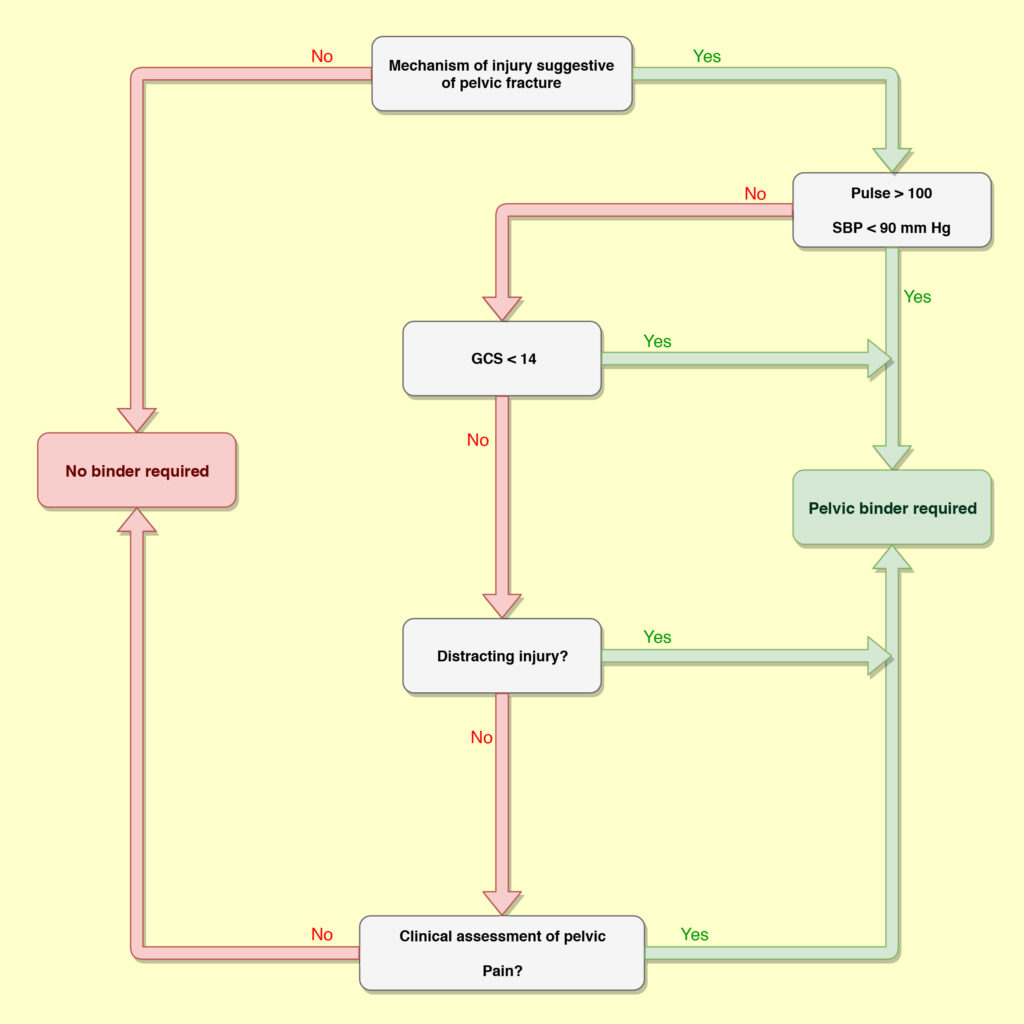

Assessment of a pelvic injury in the pre-hospital environment is through consideration of the mechanism of injury and patient presentation – if the patient appears shocked along with a significant mechanism (identified during initial scene assessment), then a pelvic binder is applied. Figure 1 illustrates a clinical decision-making framework flow diagram for when a pelvic binder is appropriate. While one recent reference documents the first reported case of haemodynamic deterioration from a pelvic binder to a LC injury (complex acetabular fracture with medial displacement of the femoral head) and advises caution in the use of pelvic binders with LC type fractures, consideration of the benefits of pelvic binders in trauma patients is an important part of the clinical decision-making process.

Identification of signs and symptoms of significant pelvic trauma simply confirm that a pelvic binder should be applied. These can include:

- Bruising and/or swelling over bony prominences, pubis, perineum and/ or scrotum;

- Discrepancy in leg length or rotation deformity of a lower limb;

- Wounds over the pelvic and bleeding from the rectum, vagina or urethra; and

- Neurological abnormalities.

As with every patient, the primary survey deals with external catastrophic haemorrhage and then significant airway and/or breathing issues prior to circulatory assessment. If the patient is hemodynamically compromised with a mechanism of injury suggestive of a pelvic injury, then a pelvic binder should be applied immediately. The pelvic binder should be considered as a treatment intervention – as it provides stability; allows clot formation; assists with tamponade; while reducing further haemorrhage and coagulopathy – instead of a packaging device – and should applied early in the patient management regime.

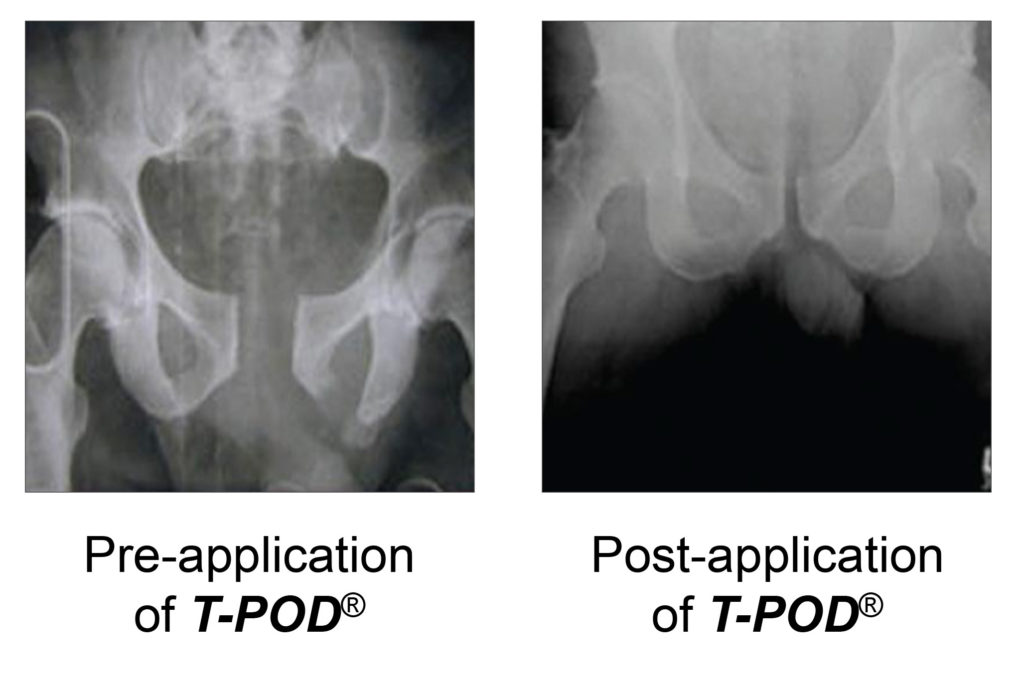

Management of pelvic fractures focuses on reducing intraperitoneal volume; reducing haemorrhage; splinting; pain reduction; and pelvic stabilisation and resuscitation. Pelvic binding devices assist with all of these by providing simultaneous circumferential compression, providing a simple alternative to surgical fixators in stabilising the pelvis and potentially allow control of unseen major haemorrhage, with the major advantage is that they can be easily applied in the pre-hospital environment. There are various commercial pelvic binders available, but the two with the strongest evidence base are the SAM splint and T-POD – in Western Australia the state ambulance service utilises the T-POD device.

Correct application of the pelvic device is essential as misplacement reduces the degree of fracture reduction. To be most effective the pelvic binder should to be placed directly to skin or just over thin underwear. It should be applied across the greater trochanters and symphysis pubis regions. The T-POD device also has clear instructions on the amount of compression that should be applied as over-reduction of the fracture increases stress on the ligaments, leading to increased haemorrhage and further injury.

Patients with suspected pelvic trauma should not be routinely log-rolled as rolling the patient can cause clot disruption and further haemodynamic compromise. Log-rolling is only considered appropriate when turning the patient on to their back or side to access and manage the airway. Additionally, any motion between the torso and lower limbs can result in displacement of the pelvic ring fracture, threatening coagulation and blood clot formation. To eliminate the likelihood of the patient requiring to be log-rolled at ED, the patient should not be transported on a spinal or long board. Additionally, the tissue under the binder is at risk of pressure necrosis is higher for patients transported on spinal boards, especially if they have low blood pressure.

Pelvic binders should ideally not be removed until the patient is hemodynamically stable, normothermic and not coagulapathic. It has been suggested that for every three minutes of hemodynamically instability without haemorrhage control in a patient with severe blunt trauma the mortality increases by one per cent.

As pelvic injuries, especially unstable fractures, are often encountered as part of the multi-system trauma patient, general trauma management guidelines will also apply to these patients, including spinal immobilisation; airway management and breathing support; venous access and fluid therapy and sufficient analgesia.

When considering falls as a cause of pelvic injuries, it is important that low falls are not ignored as potential causes of pelvic injury. Pelvic fractures, especially lateral compression fractures, are relatively common in the elderly patient, along with higher rates of clinically significant haemorrhage. In elderly patients, the sensitivity of plain trauma series pelvic films for identifying posterior pelvic ring fractures in very low, allowing up to 97 per cent of posterior pelvic fractures bring missed in the presence of pubic rami fractures.

Pelvic fractures are rare in paediatric patients, but may occur in high energy trauma. The same management principles apply for paediatric patients, however, the T-POD will not fit children lighter than 23 Kg (approximately 7 years old). In these circumstances, should not other pelvic binder be available, circumferential pelvic sheeting is an option – a folded sheet is placed under the patient, between the iliac crests and greater trochanters, two team members then cross the sheet over the pubic symphysis and pull the sheet firmly, before twisting the ends and securing.

Pelvic fractures can range from mild to life-threatening injuries, depending on the mechanism of injury, severity of vascular injury and extent of organ damage. Due to the challenge of diagnosing pelvic injuries in the pre-hospital environment, management is largely dependent on assessing mechanism of injury and maintaining a high index of suspicion. Pelvic binders play a vital and rapidly applied stabilisation management tool for pelvic trauma, which combined with generic trauma management principles, provide calculated resuscitation and timely transport of critically injured patients. While patients with pelvic fractures normally fall under an ambulance service’s trauma bypass guideline – aimed at minimising transport time to a trauma centre – critically injured, especially peri-arrest, patients along with those transported by volunteer ambulance crews will often be transported to local hospitals.

This article was initially written by PaReflectionEd authors for the Midland Hospital ED Clinical Education Newsletter in September 2018.

References

Scott I, Porter K, Laird C, Greaves I, Bloch M. The pre-hospital management of pelvic fractures: initial consensus statement. Journal of Paramedic Practice. 2014 May;6(5):248-52.

Fitzgerald M, Esser M, Russ M, Mathew J, Varma D, Wilkinson A, Mannambeth RV, Smit D, Bernard S, Mitra B. Pelvic trauma mortality reduced by integrated trauma care. Emergency Medicine Australasia. 2017 Aug;29(4):444-9.

Gumm K, Judson R, Bucknill A, Oppy A, Walsh M, Pascoe D. Haemodynamically unstable pelvic fracture guideline. The Royal Melbourne Hospital. 2018 March.

Gumm K, Liersch K, Judson R, Bucknill A, Oppy A. Pelvic binder guideline. The Royal Melbourne Hospital. 2016 August.

Gerecht R, Larrimore A, Steuerwald M. Critical Management of Deadly Pelvic Injuries. Journal of Emergency Medical Services website. Published. 2014 Dec;2.

Nickson C. Pelvic Trauma. Life in the Fast Lane. 6 June 2016

Garner AA, Hsu J, McShane A, Sroor A. Hemodynamic Deterioration in Lateral Compression Pelvic Fracture After Prehospital Pelvic Circumferential Compression Device Application. Air Medical Journal. 2017 Sep 1;36(5):272-4.

Carpenter CR, Arendts G, Hullick C, Nagaraj G, Cooper Z, Burkett E. Major trauma in the older patient: Evolving trauma care beyond management of bumps and bruises. Emergency Medicine Australasia. 2017 Aug;29(4):450-5.

The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne. Trauma – Early management of pelvic injuries in children. The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne, Victoria. Accessed 20 August 2018.