Research published in June include a comparison of airway management techniques; assessing stroke severity; how thrombosis time in stroke is increased due to high blood pressure; a comparison of the recognition of airway structures; a review of the NICE major trauma guidelines; how computer interpretation can affect paramedic identification of STEMIs; use of capnography in drug poisoning; ethanol administration for methanol outbreaks; a comparison of NIV by helmet and facemask; and how pain advice affects patient satisfaction.

Comparison of airway management techniques

Paramedics and emergency physicians achieved equal overall successful placement rates for all devices in this manikin study. The authors suggest that supraglottic devices could be considered as interim airway management techniques in scenes with difficult patient access or instances of failed intubation.

European Journal of Emergency Medicine: August 2016 – Volume 23 – Issue 4 – p 279–285

Background: Emergency airway management can be particularly challenging in patients entrapped in crashed cars because of limited access. The aim of this study was to analyse the feasibility of four different airway devices in various standardized settings utilized by paramedics and emergency physicians.

Methods: Twenty-five paramedics and 25 emergency physicians were asked to perform advanced airway management in a manikin entrapped in a car’s left front seat, with access to the patient through the opened driver’s door or access from the back seat. Available airway devices included Macintosh and Airtraq laryngoscopes, as well as laryngeal mask airway (LMA) Supreme and the Laryngeal Tube. The primary endpoints were successful placement, along with attempts needed to do so, and time for successful placement. The secondary endpoints included Cormack–Lehane grades and rating of the difficulty of the technique with the different devices.

Results: The overall intubation and placement success rates were equal for the Macintosh and Airtraq laryngoscopes as well as the LMA Supreme and Laryngeal Tube, with access from the back seat being superior in terms of placement time and ease of use. Supraglottic airway devices required half of the placement time and were easier to use compared with endotracheal tubes (with placement times almost >30 s). Paramedics and emergency physicians achieved equal overall successful placement rates for all devices.

Conclusion: Both scenarios of securing the airway seem suitable in this manikin study, with access from the back seat being superior. Although all airway devices were applicable by both groups, paramedics and emergency physicians, supraglottic device placement was faster and always possible at the first attempt. Therefore, the LMA Supreme and the Laryngeal Tube are attractive alternatives for airway management in this context if endotracheal tube placement fails. Furthermore, supraglottic device placement, while the patient is still in the vehicle, followed by a definitive airway once the patient is extricated would be a worthwhile alternative course of action.

Assessing stroke severity

This study examines the prediction of a large artery occlusion in patients with an acute ischaemic stroke, specifically assessing the level of consciousness, gaze palsy/ deviation and arm weakness.

Pre-hospital Acute Stroke Severity Scale to Predict Large Artery Occlusion

Stroke. 2016; 47: 1772-1776

Background and Purpose:The authors designed and validated a simple pre-hospital stroke scale to identify emergent large vessel occlusion (ELVO) in patients with acute ischemic stroke and compared the scale to other published scales for prediction of ELVO.

Methods: A national historical test cohort of 3127 patients with information on intracranial vessel status (angiography) before reperfusion therapy was identified. National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) items with the highest predictive value of occlusion of a large intracranial artery were identified, and the most optimal combination meeting predefined criteria to ensure usefulness in the prehospital phase was determined. The predictive performance of Prehospital Acute Stroke Severity (PASS) scale was compared with other published scales for ELVO.

Results: The PASS scale was composed of 3 NIHSS scores: level of consciousness (month/age), gaze palsy/deviation, and arm weakness. In derivation of PASS 2/3 of the test cohort was used and showed accuracy (area under the curve) of 0.76 for detecting large arterial occlusion. Optimal cut point ≥2 abnormal scores showed: sensitivity=0.66 (95% CI, 0.62–0.69), specificity=0.83 (0.81–0.85), and area under the curve=0.74 (0.72–0.76). Validation on 1/3 of the test cohort showed similar performance. Patients with a large artery occlusion on angiography with PASS ≥2 had a median NIHSS score of 17 (interquartile range=6) as opposed to PASS <2 with a median NIHSS score of 6 (interquartile range=5). The PASS scale showed equal performance although more simple when compared with other scales predicting ELVO.

Conclusions: The PASS scale is simple and has promising accuracy for prediction of ELVO in the field.

High blood pressure prolongs time to thrombolysis

Pre-hospital blood pressure control could be a potential area for improvement to reduce door-to-needle times in patients with acute ischemic stroke – in this study authors found that high blood pressure can reduce the door-to-needle time by, on average, 30 minutes.

The American Journal of Emergency Medicine , Volume 34 , Issue 7 , 1268 – 1272

Per the American Heart Association guidelines, blood pressure (BP) should be less than 185/110 to be eligible for stroke thrombolysis. No studies have focused on pre-hospital BP and its impact on door to needle (DTN) times. The authors hypothesised that DTN times would be longer for patients with higher pre-hospital BP.

Methods: The authors conducted a retrospective review of acute ischemic stroke patients who presented between January 2010 and December 2010 to our emergency department (ED) through emergency medical services within 3 hours of symptom onset. Patients were categorized into 2 groups: prehospital BP greater than or equal to 185/110 (group 1) and less than 185/110 (group 2). Blood pressure records were abstracted from emergency medical services run sheets. Primary outcome measure was DTN time, and secondary outcome measures were modified Rankin Score at discharge, symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage, length of stay in stroke unit, and discharge disposition.

Results: A total of 107 consecutive patients were identified. Of these, 75 patients (70%) were thrombolysed. Mean DTN times were significantly higher in group 1 (adjusted mean [95% confidence interval], 86 minutes [76-97] vs 56 minutes [45-68]; P < .0001). A greater number of patients required anti-hypertensive medications before thrombolysis in the ED in group 1 compared to group 2 (54% vs 27%; P = .02).

Conclusion: Higher pre-hospital BP is associated with prolonged DTN times and DTN time remains prolonged if pre-hospital BP greater than or equal to 185/110 is untreated before ED arrival. Pre-hospital BP control could be a potential area for improvement to reduce DTN times in patients with acute ischemic stroke.

Recognition of airway structures

Correct recognition of the airway structures is essential, regardless of whether you are a paramedic, trainee anaesthetist or anaesthetist, regardless of the equipment used to visualise the vocal cords. While the majority of participants (and all staff anesthetists) is this research correctly recognised the vocal cords in both the circulated and non-circulated airway, it stresses the importance of exposure to both circulated and non-circulated airways during training.

Visual recognition of anatomical structures in a circulated and in a non-circulated airway

The American Journal of Emergency Medicine , Volume 34 , Issue 7 , 1236 – 1240

Pre-hospital airway management is complex and complications occur frequently. Guidelines advice using waveform capnography to confirm correct tube position, but in the emergency setting this is not universally available. Continuous visualization of the airway with a video tube (VivaSight SL™) could serve as an alternative confirmation method, provided that airway structures are properly recognized. With this study we wanted to investigate whether airway management practitioners were able to recognize anatomical structures both in a circulated and in a non-circulated airway.

Methods: Ten staff anesthetists, ten trainee anesthetists and ten paramedics were asked to examine four pictures of a circulated airway, obtained in a healthy patient and four pictures of a non-circulated airway, obtained in a human cadaver. Correct recognition of the tube position in the airway was scored.

Results: Anatomic structures in the circulated airway were more often recognized than in the non-circulated airway, 90% vs. 43% respectively (P < .001). Overall, anesthetists performed better than paramedics (P = .009), but also when only pictures of the non-circulated model were taken into account (P = .007). The majority of participants and all staff anesthetists correctly recognized the vocal cords in both the circulated and non-circulated airway.

Conclusions: Pictures of a circulated airway were more often recognized than of a non-circulated airway and personnel with a daily routine in airway management performed better than personnel with less frequent exposure. Future research should determine whether continuous visualization of the airway with a video tube could reduce the number of misplaced tracheal tubes in pre-hospital airway management.

Major trauma assessment and intial management

This article summarises the most recent recommendations from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) on the assessment and initial management of major trauma. These guidelines sit as part of a suite of trauma guidelines and alongside the previously published guidelines on head injury, but readers should be aware that they are written in the context of the NHS, where trauma care has been organised into major trauma networks. The authors focus on two central themes of the guidelines – the assessment of a patient with major trauma and the management of patients who are actively bleeding.

Assessment and initial management of major trauma: summary of NICE guidance

Trauma is a major contributor to the global burden of disease. Those who experience major trauma have serious and often multiple injuries associated with a strong possibility of death or disability. Nationally there are around 20 000 cases of major trauma per year in England, and over a quarter of these result in deaths. Trauma care is a developing field, and recent civilian and military research has led to changes in the assessment and management of severely injured patients.

The link to the full guidelines can be found at: NICE guideline recommendations

Specific pre-hospital considerations include:

Drug‑assisted rapid sequence induction of anaesthesia and intubation.

Use drug-assisted rapid sequence induction (RSI) of anaesthesia and intubation as the definitive method of securing the airway in patients with major trauma who cannot maintain their airway and/or ventilation.

If RSI fails, use basic airway manoeuvres and adjuncts and/or a supraglottic device until a surgical airway or assisted tracheal placement is performed.

Aim to perform RSI as soon as possible and within 45 minutes of the initial call to the emergency services, preferably at the scene of the incident. If RSI cannot be performed at the scene:

– consider using a supraglottic device if the patient’s airway reflexes are absent

– use basic airway manoeuvres and adjuncts if the patient’s airway reflexes are present or supraglottic device placement is not possible

– transport the patient to a major trauma centre for RSI provided the journey time is 60 minutes or less

– only divert to a trauma unit for RSI before onward transfer if a patent airway cannot be maintained or the journey time to a major trauma centre is more than 60 minutes.

Management of chest trauma in pre‑hospital settings

Use clinical assessment to diagnose pneumothorax for the purpose of triage or intervention.

Consider using eFAST (extended focused assessment with sonography for trauma) to augment clinical assessment only if a specialist team equipped with ultrasound is immediately available and onward transfer will not be delayed. Be aware that a negative eFAST of the chest does not exclude a pneumothorax.

Only perform chest decompression in a patient with suspected tension pneumothorax if there is haemodynamic instability or severe respiratory compromise.

Use open thoracostomy instead of needle decompression if the expertise is available, followed by a chest drain via the thoracostomy in patients who are breathing spontaneously.

Observe patients after chest decompression for signs of recurrence of the tension pneumothorax.

In patients with an open pneumothorax:

– cover the open pneumothorax with a simple occlusive dressing and

– observe for the development of a tension pneumothorax.

Management of haemorrhage in pre‑hospital and hospital settings

Use simple dressings with direct pressure to control external haemorrhage.

In patients with major limb trauma use a tourniquet if direct pressure has failed to control life‑threatening haemorrhage.

If active bleeding is suspected from a pelvic fracture after blunt high‑energy trauma:

– apply a purpose‑made pelvic binder or

– consider an improvised pelvic binder, but only if a purpose‑made binder does not fit.

Use intravenous tranexamic acid as soon as possible in patients with major trauma and active or suspected active bleeding. Do not use intravenous tranexamic acid more than 3 hours after injury in patients with major trauma unless there is evidence of hyperfibrinolysis.

Circulatory access in pre‑hospital settings

For circulatory access in patients with major trauma in pre‑hospital settings: use peripheral intravenous access or if peripheral intravenous access fails, consider intra‑osseous access.

For circulatory access in children (under 16s) with major trauma, consider intra‑osseous access as first‑line access if peripheral access is anticipated to be difficult.

For patients with active bleeding use a restrictive approach to volume resuscitation until definitive early control of bleeding has been achieved.

In pre-hospital settings, titrate volume resuscitation to maintain a palpable central pulse (carotid or femoral).

For patients who have haemorrhagic shock and a traumatic brain injury: if haemorrhagic shock is the dominant condition, continue restrictive volume resuscitation or if traumatic brain injury is the dominant condition, use a less restrictive volume resuscitation approach to maintain cerebral perfusion.

Fluid replacement in pre‑hospital

In pre-hospital settings only use crystalloids to replace fluid volume in patients with active bleeding if blood components are not available.

For adults (16 or over) use a ratio of 1 unit of plasma to 1 unit of red blood cells to replace fluid volume. For children (under 16s) use a ratio of 1 part plasma to 1 part red blood cells, and base the volume on the child’s weight.

Pain assessment and management

Assess pain regularly in patients with major trauma using a pain assessment scale suitable for the patient’s age, developmental stage and cognitive function.

Continue to assess pain in hospital using the same pain assessment scale that was used in the pre‑hospital setting.

For patients with major trauma, use intravenous morphine as the first‑line analgesic and adjust the dose as needed to achieve adequate pain relief.

If intravenous access has not been established, consider the intranasal route for atomised delivery of diamorphine or ketamine.

Consider ketamine in analgesic doses as a second‑line agent.

Capnography in drug poisoning

The authors identified that, in isolation, EtCO2 was less able to predict complications than the Glasgow Coma Scale score in drug poisoning. However, how often are individual components of a patient assessment considered in isolation – the EtCO2 numerical values should also ideally be considered in association with the capnography waveform along with airway patency, respiratory rate and effort, consciousness and cardiac output.

Annals of Emergency Medicine. Volume 68, Issue 1, July 2016, Pages 62–70.e1

The authors studied the performance of capnometry in the detection of early complications after deliberate drug poisoning.

Methods: This was a prospective cohort study of self-poisoned adult patients who presented at an emergency department (ED) between April 20, 2012, and May 6, 2014. Patients who ingested at least 1 neurologic or respiratory depressant drug were included. The primary outcome was the predictive value of an end tidal CO2 (EtCO2) measurement greater than or equal to 50 mm Hg for the detection of early complications defined a priority by hypoxia requiring oxygen greater than or equal to 3 L/min, bradypnoea less than or equal to 10 breaths/min, or ICU admission after intubation or antidote administration because of unresponsiveness to pain or respiratory arrest. Consciousness scales and clinical data were recorded at admission and every 30 minutes. Noninvasive EtCO2 was continuously measured for 2 hours after inclusion unless the patient was admitted to the ICU. Patients and physicians were blinded to EtCO2 values.

Results: Two hundred one patients were included, 35 of whom exhibited at least 1 complication. An EtCO2 measurement greater than or equal to 50 mm Hg predicted the onset of a complication, with a sensitivity of 46% (95% confidence interval [CI] 29% to 63%) and a specificity of 80% (95% CI 73% to 86%), leading to a positive predictive value of 33% (95% CI 20% to 48%) and a negative predictive value of 88% (95% CI 81% to 92%). EtCO2 was less able to predict complications than the Glasgow Coma Scale score at inclusion.

Conclusion: Capnometry in isolation does not provide adequate prediction of early complications in self-poisoned patients referred to the ED. A dynamic minute-by-minute assessment of EtCO2 could be more predictive.

Ethanol administration for methanol outbreaks

In areas where methanol outbreaks are likely to occur, out-of-hospital ethanol administration might be appropriate, especially with a positive association identified between out-of-hospital ethanol administration and improved clinical outcome.

Use of Out-of-Hospital Ethanol Administration to Improve Outcome in Mass Methanol Outbreaks

Annals of Emergency Medicine. Volume 68, Issue 1, July 2016, Pages 52–61

Methanol poisoning outbreaks are a global public health issue, with delayed treatment causing poor outcomes. Out-of-hospital ethanol administration may improve outcome, but the difficulty of conducting research in outbreaks has meant that its effects have never been assessed. The authors studied the effect of out-of-hospital ethanol in patients treated during a methanol outbreak in the Czech Republic between 2012 and 2014.

Methods: This was an observational case-series study of 100 hospitalized patients with confirmed methanol poisoning. Out-of-hospital ethanol as a “first aid antidote” was administered by paramedic or medical staff before the confirmation of diagnosis to 30 patients; 70 patients did not receive out-of-hospital ethanol from the staff (12 patients self-administered ethanol shortly before presentation).

Results: The state of consciousness at first contact with paramedic or medical staff, delay to admission, and serum methanol concentration were similar among groups. The median serum ethanol level on admission in the patients with out-of-hospital administration by paramedic or medical staff was 84.3 mg/dL (interquartile range 32.7 to 129.5 mg/dL). No patients with positive serum ethanol level on admission died compared with 21 with negative serum ethanol level (0% versus 36.2%). Patients receiving out-of-hospital ethanol survived without visual and central nervous system sequelae more often than those not receiving it (90.5% versus 19.0%). A positive association was present between out-of-hospital ethanol administration by paramedic or medical staff, serum ethanol concentration on admission, and both total survival and survival without sequelae of poisoning.

Conclusion: The authors found a positive association between out-of-hospital ethanol administration and improved clinical outcome. During mass methanol outbreaks, conscious adults with suspected poisoning should be considered for administration of out-of-hospital ethanol to reduce morbidity and mortality.

Hospital pre-alert for stroke

This open access study identified that while up to half of the patients presenting with suspected stroke are pre-alerted by the emergency medical services, on some occasions this was against the instruction of locally agreed rapid transfer protocols, resulting in disagreements with hospital staff during handover. It is important that both out-of-hospital and hospital practitioners have a good understanding, and the principles that underlie them, of protocols and guidelines to facilitate effective collaborative working.

Prevalence and predictors of hospital prealerting in acute stroke: a mixed methods study

Background: Thrombolysis can significantly reduce the burden of stroke but the time window for safe and effective treatment is short. In patients travelling to hospital via ambulance, the sending of a ‘pre-alert’ message can significantly improve the timeliness of treatment.

Objective: Examine the prevalence of hospital prealerting, the extent to which prealert protocols are followed and what factors influence emergency medical services (EMS) staff’s decision to send a prealert.

Methods: Cohort study of patients admitted to two acute stroke units in West Midlands (UK) hospitals using linked data from hospital and EMS records. A logistic regression model examined the association between prealert eligibility and whether a prealert message was sent. In semistructured interviews, EMS staff were asked about their experiences of patients with suspected stroke.

Results: Of the 539 patients eligible for this study, 271 (51%) were recruited. Of these, only 79 (29%) were eligible for pre-alerting according to criteria set out in local protocols but 143 (53%) were pre-alerted. Increasing number of Face, Arm, Speech Test symptoms (1 symptom, OR 6.14, 95% CI 2.06 to 18.30, p=0.001; 2 symptoms, OR 31.36, 95% CI 9.91 to 99.24, p<0.001; 3 symptoms, OR 75.84, 95% CI 24.68 to 233.03, p<0.001) and EMS contact within 5 h of symptom onset (OR 2.99, 95% CI 1.37 to 6.50 p=0.006) were key predictors of pre-alerting but eligibility for pre-alert as a whole was not (OR 1.92, 95% CI 0.85 to 4.34 p=0.12). In qualitative interviews, EMS staff displayed varying understanding of pre-alert protocols and described frustration when their interpretation of the pre-alert criteria was not shared by ED staff.

Conclusions: Up to half of the patients presenting with suspected stroke in this study were prealerted by EMS staff, regardless of eligibility, resulting in disagreements with ED staff during handover. Aligning the expectations of EMS and ED staff, perhaps through simplified prealert protocols, could be considered to facilitate more appropriate use of hospital prealerting in acute stroke.

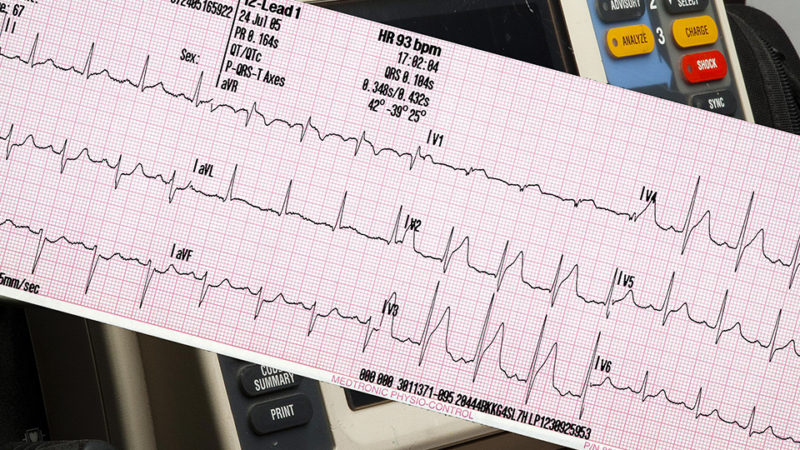

STEMI recognition by paramedics

Computer interpretation of 12-lead ECGs influences paramedic identification of STEMI may not be beneficial, while helpful if the interpretation is correct, an incorrect interpretation may negatively influence a paramedic’s diagnosis.

Emerg Med J 2016;33:471-476

Background: The appropriate management of patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) depends on accurate interpretation of the 12-lead ECG by paramedics. Computer interpretation messages on ECGs are often provided, but the effect they exert on paramedics’ decision-making is not known. The objective of this study was to assess the feasibility of using an online assessment tool, and collect pilot data, for a definitive trial to determine the effect of computer interpretation messages on paramedics’ diagnosis of STEMI.

Methods: The Recognition of STEMI by Paramedics and the Effect of Computer inTerpretation (RESPECT) feasibility study was a randomised crossover trial using a bespoke, web-based assessment tool. Participants were randomly allocated 12 of 48 ECGs, with an equal mix of correct and incorrect computer interpretation messages, and STEMI and STEMI-mimics. The nature of the responses required a cross-classified multi-level model.

Results: 254 paramedics consented into the study, 205 completing the first phase and 150 completing phase two. The adjusted OR for a correct paramedic interpretation, when the computer interpretation was correct (true positive for STEMI or true negative for STEMI-mimic), was 1.80 (95% CI 0.84 to 4.91) and 0.58 (95% CI 0.41 to 0.81) when the computer interpretation was incorrect (false positive for STEMI or false negative for STEMI-mimic). The intraclass correlation coefficient for correct computer interpretations was 0.33 for participants and 0.17 for ECGs, and for incorrect computer interpretations, 0.06 for participants and 0.01 for ECGs.

Conclusions: Determining the effect of computer interpretation messages using a web-based assessment tool is feasible, but the design needs to take clustered data into account. Pilot data suggest that computer messages influence paramedic interpretation, improving accuracy when correct and worsening accuracy when incorrect.

Pain advice and patient satisfaction

Emerg Med J 2016;33:453-457

Objective: The authors aimed to provide pain advice (‘The treatment of pain is very important and be sure to tell the staff when you have pain’) as an intervention and evaluate its effect upon patient satisfaction. The purpose of this pilot trial was to ensure the design and methods of a future trial are sound, practicable and feasible.

Method: The authors undertook a pilot, randomised, controlled, clinical intervention trial in a single ED. The control arm received standard care. The intervention arm received standard care plus pain advice from an independent investigator. All patients and treating ED staff were blinded to patient enrolment. Patient satisfaction with their pain management (six-point ordinal scale) was measured 48 h post-ED discharge, by a blinded researcher. The primary outcome was satisfaction with pain management.

Results: Of the 280 and 275 patients randomised to the control and intervention arms, respectively, 196 and 215 had complete data, respectively. 77.6% (152/196) and 88.8% (191/215) of patients reported being provided with pain advice, respectively (difference 11.3% (95% CI 3.6 to 19.0)). The intervention was associated with absolute and relative increases in patient satisfaction of 6.3% and 14.2%, respectively. 91.3% (179/196) and 76.3% (164/215) of patients who were/were not very satisfied reported having received ‘pain advice’ (difference 15.0% (95% CI 7.6 to 22.5)).

Conclusions: The intervention to provide pain advice resulted in a non-significant increase in patient satisfaction. A larger multi-centre trial is feasible and is recommended to further explore the effects of provision of pain advice.

NIV by helmet rather than a mask

Treating patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome with helmet non-invasive ventilation not only resulted in a significant reduction of intubation rates but also a statistically significant reduction in 90-day mortality.

Effect of Noninvasive Ventilation Delivered by Helmet vs Face Mask on the Rate of Endotracheal Intubation in Patients With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome

A Randomized Clinical Trial

JAMA. 2016;315(22):2435-2441

Non-invasive ventilation (NIV) with a face mask is relatively ineffective at preventing endotracheal intubation in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Delivery of NIV with a helmet may be a superior strategy for these patients.

Objective: To determine whether NIV delivered by helmet improves intubation rate among patients with ARDS.

Design, Setting, and Participants: Single-center randomized clinical trial of 83 patients with ARDS requiring NIV delivered by face mask for at least 8 hours while in the medical intensive care unit at the University of Chicago between October 3, 2012, through September 21, 2015.

Interventions: Patients were randomly assigned to continue face mask NIV or switch to a helmet for NIV support for a planned enrollment of 206 patients (103 patients per group). The helmet is a transparent hood that covers the entire head of the patient and has a rubber collar neck seal. Early trial termination resulted in 44 patients randomized to the helmet group and 39 to the face mask group.

Main Outcomes and Measures: The primary outcome was the proportion of patients who required endotracheal intubation. Secondary outcomes included 28-day invasive ventilator–free days (ie, days alive without mechanical ventilation), duration of ICU and hospital length of stay, and hospital and 90-day mortality.

Results: Eighty-three patients (45% women; median age, 59 years; median Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation [APACHE] II score, 26) were included in the analysis after the trial was stopped early based on predefined criteria for efficacy. The intubation rate was 61.5% (n = 24) for the face mask group and 18.2% (n = 8) for the helmet group (absolute difference, −43.3%; 95% CI, −62.4% to −24.3%; P < .001). The number of ventilator-free days was significantly higher in the helmet group (28 vs 12.5, P < .001). At 90 days, 15 patients (34.1%) in the helmet group died compared with 22 patients (56.4%) in the face mask group (absolute difference, −22.3%; 95% CI, −43.3 to −1.4; P = .02). Adverse events included 3 interface-related skin ulcers for each group (ie, 7.6% in the face mask group had nose ulcers and 6.8% in the helmet group had neck ulcers).

Conclusions and Relevance: Among patients with ARDS, treatment with helmet NIV resulted in a significant reduction of intubation rates. There was also a statistically significant reduction in 90-day mortality with helmet NIV. Multi-center studies are needed to replicate these findings.

Paramedic involvement with home births

This study highlights the need for cooperative collaboration between maternity and ambulance services, while paramedics attended a small number of women having intended home births in the context of their overall workload they provided clinical support for home birth midwives, performing a range of procedures for mothers and infants.

Paramedics׳ involvement in planned home birth: A one-year case study

Midwifery. July 2016 Volume 38, Pages 71–77

Objective: To report findings from a study performed prior to the introduction of publicly funded home birth programmes in Victoria, Australia, that investigated the incidence of planned home births attended by paramedics and explored the clinical support they provided as well as the implications for education and practice.

Methods: Retrospective data previously collected via an in-field electronic patient care record (VACIS®) was provided by a state-wide ambulance service. Cases were identified via a comprehensive filter, manually screened and analysed using SPSS version 19.

Results: Over a 12-month period paramedics attended 26 intended home births. Eight women were transported in labour, most for failure to progress. Three called the ambulance service and their pre-organised midwife simultaneously. Paramedics were required for a range of complications including post partum haemorrhage, perineal tears and neonatal resuscitation. Procedures performed for mothers included IV therapy and administering pain relief. For infants, paramedics performed intermittent positive pressure ventilation, endotracheal intubation and external cardiac compression. Of the 23 women transferred to hospital, 22 were transported to hospital within 32 minutes.

Conclusions: Findings highlight that paramedics can provide clinical support, as well as efficient transportation, during perinatal emergencies at planned home births. Cooperative collaboration between ambulance services, privately practising midwives and maternity services to develop guidelines for emergency clinical support and transportation service may minimise risk associated with planned home births. This could also lead to opportunities for interprofessional education between midwives and paramedics.