While recently researching paediatric asthma management, we came across a statement in the Australian Asthma Handbook which not only caused us to examine our current practice, but might also influence the incorrect opinion that pressurised metered dose inhalers (pMDI) are less effective than nebulised bronchodilators. Reading the evidence also caused us to review our technique for pMDI use, especially reading that only 15–69 per cent of healthcare professionals (across all disciplines) can demonstrate correct inhaler use 1.

New plastic spacers should be washed with detergent to remove electrostatic charge so they are ready for use when needed. In an emergency situation, if a pre-treated spacer is not available, prime the spacer before use by firing at least 10 puffs of salbutamol into the spacer 2.

The Australian Asthma Handbook (produced by the National Asthma Council Australia to translate best practice, evidence-based guidance into practical advice for primary care health professionals) also specifies that the “at least 10 puffs” is actually an arbitrary number, as there is insufficient evidence to enable a precise guideline.

Plastic spacers have electrostatic surface charge, which reduces the proportion of medicine available for delivery to the airway and has been found to reduce the lung dose by at least two fold 3. Whilst it is now recognised that individual spacer devices may vary in their emission of fine mass particles and their propensity to accumulate static charge, there is still little clinical evidence on which to base recommendations about using one device over another. Until there are studies documenting the clinical consequences, if any, of using different spacer devices with or without measures to reduce static charge, it seems sensible to follow manufacturers’ guidance and national guidelines 4.

Priming or washing spacers to reduce electrostatic charge before use for the first time is only required for standard plastic chambers – manufacturers’ guidance, contained with the spacer packaging, should state if pre-treatment is required. Antistatic polymer spacers (such as Able A2A; AeroChamber Plus; Breathe Easy) and disposable cardboard spacers do not require treatment to reduce electrostatic charge. In addition to priming the spacer, some pMDIs need to be shaken before actuation (omitting shaking can affect the dose uniformity) and primed on first use (or after several days or weeks of disuse) by simply discharging two to four doses into the surrounding air, away from the patient 5.

To prepare the spacer, dismantle and wash in warm water and dishwashing detergent before allowing to air dry without rinsing or wiping. Wiping can increase the electrostatic charge on the inside of the spacer, which can reduce the available dose.

Apart from life-threatening asthma, pMDIs are the preferred management technique; not only because they are just as effective as nebulisers, but also because they are associated with fewer side- effects and reduced risk of nosocomial aerosol infection. Many organisations’ infection control policies limit the use of nebulisers – particularly in patients exhibiting symptoms of influenza-like illness (ILI) – to minimise the spread of respiratory tract infections to staff and patients. The use of nebulisers was associated with a major outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Hong Kong in March 2003 6.

Salbutamol delivered by pMDI is at least as effective as salbutamol delivered via nebuliser in patients with moderate to severe acute asthma who do not require ventilation. When considering the benefits of replacing nebulisers with pMDI-spacers, Alhaider et al (2014), identified that patients in the spacer group had a significantly lower admission rate (5% versus 20% in the nebuliser group), received fewer treatments, had a lower mean increase in heart rate and were less likely to receive steroids 7.

In addition to eliminating the problem of co-ordinating activation of pMDIs with inhalation, the use of a spacer increases the time between expulsion of the aerosolised particles from the pMDI and their inhalation. This facilitates evaporation of the particles to a size capable of penetrating through the entire bronchial tree as far as the alveoli, specifically with mass median diameter less than ~5 microns – the particles emitted directly from a pMDI device are initially much larger. It also facilitates slow inhalation of the evaporated particles into the lungs, which is essential if they are to negotiate beyond the right-angle bend between horizontal emission from the spacer device and the vertical passage through the larynx 4.

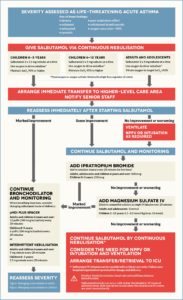

Guideline summary for the management of asthma – adults, children and life-threatening 2

While the introduction of cardboard spacers has reduced the use of plastic spacers and the requirement for washing or priming, they have not been eliminated – some cardboard spacers are not suitable for young children as no mask can be attached. If you are unsure as to whether you have an anti-static polymer spacer, or whether the plastic spacer has been washed, simply prime it before use.

- Price, D., S. Bosnic-Anticevich, A. Briggs, Henry Chrystyn, C. Rand, G. Scheuch, J. Bousquet, and Inhaler Error Steering Committee. (2013). Inhaler competence in asthma: common errors, barriers to use and recommended solutions. Respiratory medicine, 107(1), 37-46.

- National Asthma Council Australia. Australian Asthma Handbook, Version 1.2. National Asthma Council Australia, Melbourne, 2016. Website. Available from: http://www.asthmahandbook.org.au

- Anhøj, J., Bisgaard, H., & Lipworth, B. J. (1999). Effect of electrostatic charge in plastic spacers on the lung delivery of HFA-salbutamol in children. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 47(3), 333–336.

- Levy, M. L., Dekhuijzen, P. N. R., Barnes, P. J., Broeders, M., Corrigan, C. J., Chawes, B. L., … Pedersen, S. (2016). Inhaler technique: facts and fantasies. A view from the Aerosol Drug Management Improvement Team (ADMIT). NPJ Primary Care Respiratory Medicine, 26, 16017.

- Laube, B. L., Janssens, H. M., de Jongh, F. H., Devadason, S. G., Dhand, R., Diot, P., … & Chrystyn, H. (2011). What the pulmonary specialist should know about the new inhalation therapies.

- Alhaider, S. A., Alshehri, H. A., & Al-Eid, K. (2014). Replacing nebulizers by MDI-spacers for bronchodilator and inhaled corticosteroid administration: Impact on the utilization of hospital resources. International Journal of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 1(1), 26-30.